By a bit of good luck, I’ve been reading Originals by Adam Grant in the last few days. As a book about original thinking, personal development and change-making, it might not immediately strike you as a relevant read at election time. But here I am, finding myself gleaning important reminders at a time when so many of us are just trying to make sense of the results of the 2022 midterm elections in America.

Let’s start by re-capping what’s going on in the real world:

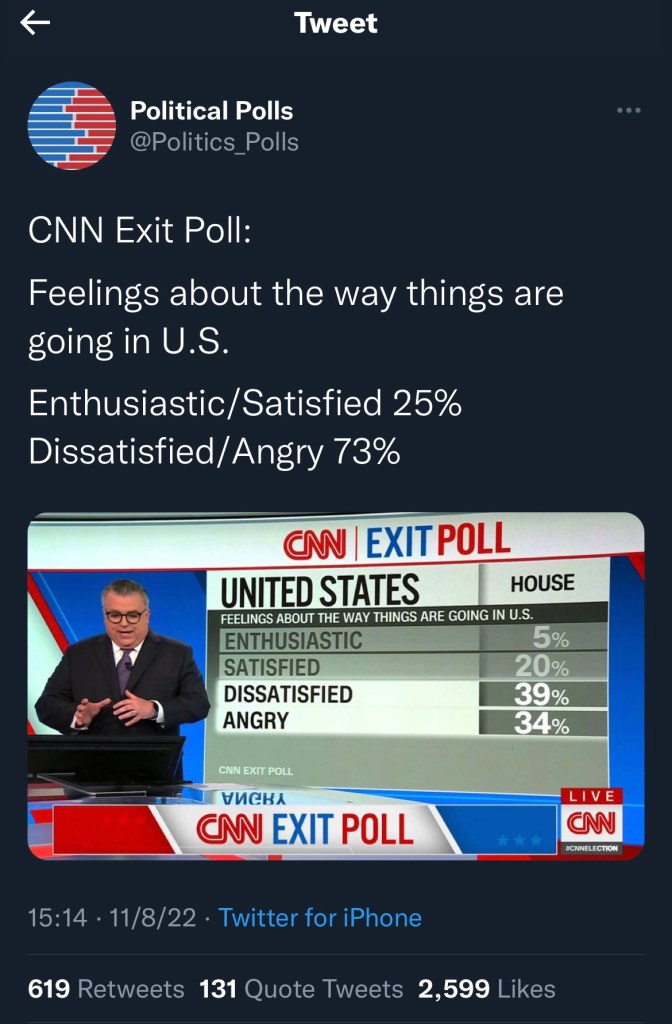

In what had promised to be a sweeping rebuke of the Biden administration, political professionals everywhere are scratching their heads on a whole host of mixed signals coming from the electorate. On election day, CNN exit polls were reporting more than 70% of respondents claiming they were dissatisfied, even angry, about the way things are going in the U.S.

As the day unfolded, and before actual results began rolling in, pundits were interpreting that in a somewhat traditional way: negative feelings mean the party in power will lose a significant number of seats in the legislature. Historically, and especially when a President is seeing low approval ratings, this holds true. It’s what many in the business expected.

But what happened? Well, not a red wave.

In my own home state of Ohio, Republicans saw sweeping victories statewide. But they also witnessed stunning defeats: a longtime Cincinnati area Republican Congressman was upset in his race, while an entrenched Democrat in the Toledo area fought off the challenges of a Trump endorsed challenger in a newly more conservative district. In a brand new iteration of Ohio’s 13th congressional district, a similar dynamic played out – in a district that was truly competitive for Republicans to pick up.

Nationally, many of the same trends held, with Republicans failing to pick up (as of yet) victories in many poachable districts. And as we wait for additional results to trickle in over the coming days and weeks, what was supposed to be a strong Republican majority seems to be shrinking.

For the record, here’s the prediction I had sent to a colleague just last Friday:

Senate: 51-49 R/D split with a late surge by Vance in Ohio; House: 229-206 R/D split with Congresswoman Kaptur (Toledo) surviving her challenge and Congressman Chabot’s (Cincinnati) race called late with a possible upset.

Yes, I have the receipts for that prediction in my email. Those specific race call-outs panned out just that way. And while we’re waiting for the final tallies on Republican/Democrat wins and losses, things aren’t looking like Republicans will gain much ground in the national picture – at least not at 9:30pm the night after Election Day.

What was expected to be a referendum on national Democrat policies has turned into a bit of a windfall for the Biden administration. And while they will very likely still be navigating a divided government next year, the damage was supposed to be a whole heck of a lot worse.

What does that tell us, and why does it matter?

Well – I’m not sure anyone can fully answer the first of those questions. The election returns are a confusing mess, full of mixed messages. In watching hours of coverage over the last day I think just about everyone is seeing these results in whatever way suits them best. But as far as why it matters? Well, that I can answer. With a little help from Adam Grant.

The leadership challenge that arises with smaller majorities is your margin of error. If Republicans were hoping for sweeping legislative action to hold the administration in check, they’re not on track to see that right now. And the narrower their margin of victory in either chamber, the harder it will be for leaders to keep the coalition unified and moving in the same direction. It’s not a lesson Republicans should have had to learn again so soon.

Between 2011 and 2019, Republicans saw varying levels of legislative majorities through the latter three-fourths of the the Obama administration. But successive speakers (John Boehner and Paul Ryan) continually struggled to maintain cohesion in the ranks as those majorities progressed. The emergence of the Tea Party and Freedom Caucus offered an alternative to the more moderate establishment leadership, and the fracturing hampered legislative activity. (That’s a stretch when I was working for a member of congress who was an ally of John Boehner.)

As Grant observed in Originals, the similarities in their objectives led to inevitable disagreements over tactics and strategy. Unhappy with the pace of progress on their agenda, wedges developed between “establishment” and “outsider” groups within the GOP caucus. And as majority margins constricted, those differences empowered the “outsiders” to hinder compromise and incrementalism.

If the tepid nature of Tuesday’s results hold, we are about to see the pattern repeated.

Republican leaders are almost guaranteed to have their feet held to the fire by members of the caucus who are impatient with the status quo. Compromises will be unpopular and debates over tactics will certainly derail major priorities. But what does that mean for advocates and the general public?

“It’s almost certain we’ll see a government shutdown.”

Just a few weeks ago, I asked two colleagues to present to a group of advocates. One Democrat, One Republican. Both with extensive knowledge of party politics and national electorate dynamics. They’d also both held very senior roles in prominent campaigns at the federal and state level.

Toward the end of our session, I asked them to share their predictions on the likelihood of gridlock in the next congress and whether we should be worried about a government shutdown. “Absolutely. It’s almost certain we’ll see that.”

Operatives from the highest levels, and differing parties, could clearly see eye to eye that we should expect some of the worst case scenarios that have played out over the past several years. And while some are celebrating the inevitable slow-down brought on by divided government, advocates must prepare for the challenges that will present to our causes.

If we acknowledge the worst case scenarios ahead – without letting them dominate and depress our thinking – we can plan around them, and how we will react to them. We know the windows of opportunity on our key agenda items will shrink or be crowded out by situations like that. We can also make an informed assumption that in the divided government scenario that social issues will dominate the daily debate while run-of-the-mill governance takes a backseat in the press.

Yet those aren’t necessarily obstacles to our agenda. They are opportunities for us to take the time necessary to develop more thoughtful proposals, more powerful storytelling and more responsive messaging. Instead of rushing from crisis response to crisis response, divided government can be a real boon to those willing to be patient. Because even when impatience is the name of the game in the politics of a caucus, patient advocates demonstrate an ability to keep doing the most important thing in advocacy: showing up.

Especially in divided government, the ability to embrace the cumulative and iterative aspects of advocacy sets the individual – and the successful advocacy organization – apart from the crowd. Those who get really good at it can survive the doldrums better than those seeking to capitalize on controversy and infighting. It may not be as exciting, it may be less frenetic, but it’s certainly not the end of the world. Just another opportunity to be brilliant in the basics.