For the better part of a decade I had a really special opportunity. Each and every work day, I was in a position to help people.

Not because I had a special set of skills. Not because I was uniquely equipped. No. None of that. The opportunity was in front of me because I’d accepted a position working in the district office of a member of the US House of Representatives. Their name and their position gave me the chance to serve in a way few will ever get to experience.

If you didn’t know already, the district – sometimes called local or home – offices of Members of Congress are not just simply extensions of their presence in Washington, DC. In fact, many district offices won’t be aggressively engaged in the legislative work that happens in the Capitol. Where these district offices often focus is in providing constituent services. These small teams exist to help constituents who are in need of some kind of help with federal agencies.

When people say “call your congressman” because of a difficult situation, they’re telling you to call those local offices. Why?

Because they have authority.

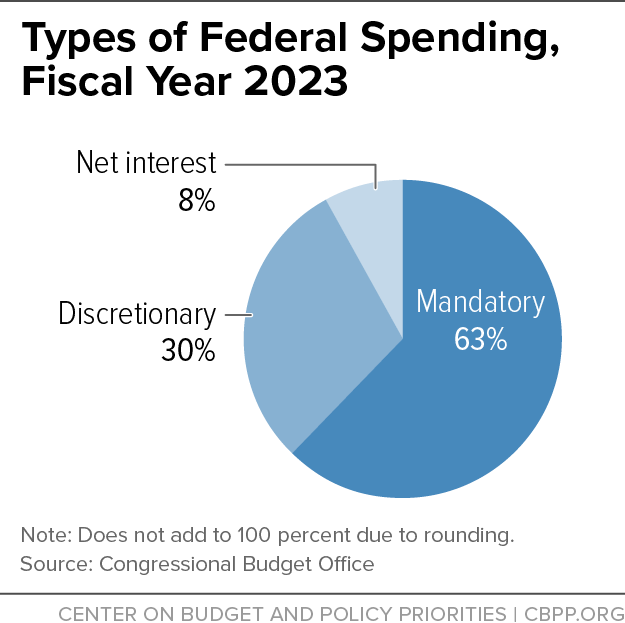

Congress holds the purse strings. They decide the funding of federal agencies and programs. And because of that, Congress is entrusted with the oversight of those programs. How do they do it?

Well, what you see on TV in Congressional hearings is one way. Committee leadership can use the committee agenda to haul executive agencies in to explain their activities. But these moments are not as common as you may think. Congress has a limited calendar of business days. Because of that, committee time is precious.

Where your Representatives and Senators can have a daily impact is the congressional inquiry process – a formal style of communicating to federal agencies and seeking their response to issues raised by constituents. It’s not sexy. But it is often quite effective. (If you missed the time I wrote about one of the more complex cases I ever handled, you should check it out here.)

The congressional inquiry process is so effective that, often times, when members retire, their accomplishments through this oversight tool are what they highlight as some of the most impactful aspects of their work. Winning in constituent services means you’re helping real people, with real problems, at the times when it matters most.

Yet, that rewarding work only exists because there are real pain points that manifest when those real people have to confront the federal bureaucracy. Social security benefits, medicare claims, veterans healthcare and pension issues, tax problems; even getting a new passport can take unexpected turns. And when these problems arise, it’s almost never at a convenient time.

So what should you do when you find yourself in that situation? If the feds aren’t helping you, how can you react? And what can you expect?

What to Do

The first step is pretty simple: pick up your smartphone. If you go to house.gov, you can search for your representative and find all of their office locations – including those back home in your district. Call any one of those local offices, and ask someone to help you with a problem. It’s that simple. That’s all it takes to get started: pick up the phone.

Those constituent services representatives will then walk you through some paperwork. You’ll have to sign a waiver for them to communicate on your behalf. You may have to supply some evidence to substantiate your claims. But once you’re past that hurdle, they can try to get to the bottom of the issue.

When to Do It

What’s important is that you don’t wait for the situation to get worse.

Too many times I heard constituents say “I wish I’d called sooner.” They added needless months of confusion and suffering to their situation. Simply because they thought their issue wouldn’t be “important” enough to warrant the attention of a member of Congress.

Malarkey.

We are not subjects of our government. We own the responsibility of holding them accountable. And any member of Congress who doesn’t believe that shouldn’t be in the game in the first place.

What You Can Expect

There’s bad news though. The process is almost never straightforward. I had an old boss who would say “we don’t do one thing a thousand times around here – we do a thousand things one time.”

Every person’s experience with a federal agency can be different. There are different factors that bring you to a point of friction. That means the solution is almost always unique to the situation. And the solution isn’t always going to be in your favor. It’s difficult to know exactly what to expect when you get started.

What you can absolutely expect is this: you’ll still have to wait a little while. Agencies are granted time periods to respond to these inquiries. So it’s not a snap of the fingers and your problem disappears. But what you gain is this: you now have an advocate on your behalf.

That staffer helping you can now be in your corner. They can help those nameless, faceless bureaucrats understand the reality of your situation. They can also help senior leaders in agencies to better develop their actions in really uncomfortable gray-area situations. Having that person at your side could just make all the difference your problem needs.

I’ll tell you straight: it’s not a perfect system. It won’t always pan out in your favor. But don’t forget this option. It’s here for you to use. Big and small problems alike – they’re all worth it. They deserve the attention of our elected officials. Use it, don’t abuse it, and it’s going to help you get past those hard times.