In my day job, I have the incredible pleasure of working with agricultural producers. American farmers and ranchers are personal heroes of mine. You see, my family sold the farm before I came along – but my dad made sure I was never too far removed from those agrarian roots.

Growing up, every month we’d visit my grandmother who still lived on a property adjacent to the old family grain farm. He’d have me walk the fields and listen to his stories of what it was like as a young man on that farm in the middle of the 20th century. He told me about hard days, short nights, and the stresses and blessings of the business. Little did I know how much those lessons would inform my work in politics down the line.

But at the same time as my dad was trying to keep me grounded, I always seemed to have my head in the stars. Any regular reader of this blog has undoubtedly come across at least one post on NASA and what’s happening in the world of human space flight. Well, I think it’s high time I bring the worlds of astronauts and agronomists together to bring perspective on an issue grabbing a great deal of attention in our national political debates: climate change and greenhouse gas emissions.

Over the past two years, an interesting conversation has been crisscrossing the countryside, and being presented as a new opportunity for agricultural producers. Across the US, farmers are being approached to participate in emerging markets that would allow them to sell credits for the carbon their crops sequester over the course of a year. Those credits, in large measure, would be sold as offsets – allowing other industries to pay, in part, for the costs of implementing new practices that allow for additional carbon sequestration in America’s rural communities.

I’ve spent a lot of time on this topic in the past year in particular. Though it started before the Biden administration, the President’s posture on climate policy is certainly pushing the debate further ahead. But, I think for the average person not engaged in these policy discussions, it’s important to know how we got here. And that’s where NASA comes in. <Insert Nerdy Glee Here>.

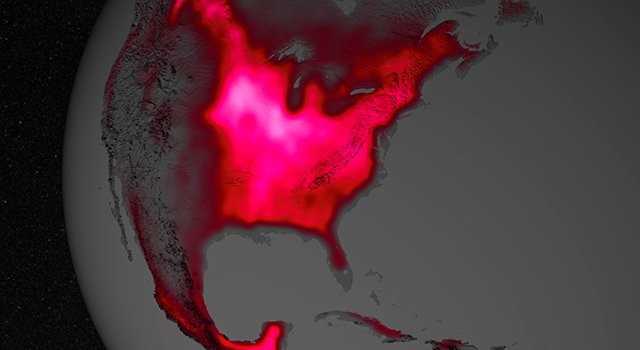

In the image above, you see a satellite view of North America reflecting data from 2007 to 2011. The fluorescence you see is NOT carbon emissions, but rather a reflection of photosynthetic activity. And for those of us struggling to remember our high school biology classes, that photosynthetic activity is how growing plants absorb the carbon they need to grow and thrive. Better yet, as the plant absorbs the carbon in our atmosphere, it transmits that carbon into the soil, offering an opportunity to sequester it in the long term.

How effective is it? Based on the data backing up the image above, it was found that photosynthesis from the U.S. Corn Belt peaks in July at levels 40 percent greater than those observed in the Amazon. The potential for sequestration in the agronomic cycle is MASSIVE. And we’ve come to realize this, in part, because of the important work performed in terrestrial research at NASA.

When it comes to NASA, most of us think of rocket launches and control rooms. But an incredible amount of NASA’s work is not about reaching further into the cosmos – instead it’s directed back toward understanding, and solving, problems right here on Earth. Since the initial findings about the Corn Belt’s productivity, the team at NASA (and some outside organizations) have invested significant resources into figuring out just where we go from here.

Right now, the political debate has room for these carbon markets – and we can thank Farmers and NASA equally for that development. In the next decade, research at the farm level and on our orbital observatories will push new developments and new advancements. The reason why I don’t live in a state of nihilistic dread about climate change is that I don’t discount the power of American innovation. In just a matter of 15 years we’ve gone from interesting data points to feasible programs. That’s the blink of an eye. I’m excited to see where we land in the next 15 years.

And if I was a betting man, I’d continue to put my money on NASA and Farmers to save the world.